This is the Strom Thurmond Fitness Center, the $38 million crown jewel of the University of South Carolina, my alma mater. (Go gamecocks! Beat Vandy!)

You can’t see it from this picture, but “The Strom” sits at the top of what we at home would call “big-ass hill.” At the bottom of the hill like two important tourist attractions for the University of South Carolina: Greek housing and lots of parking garages.

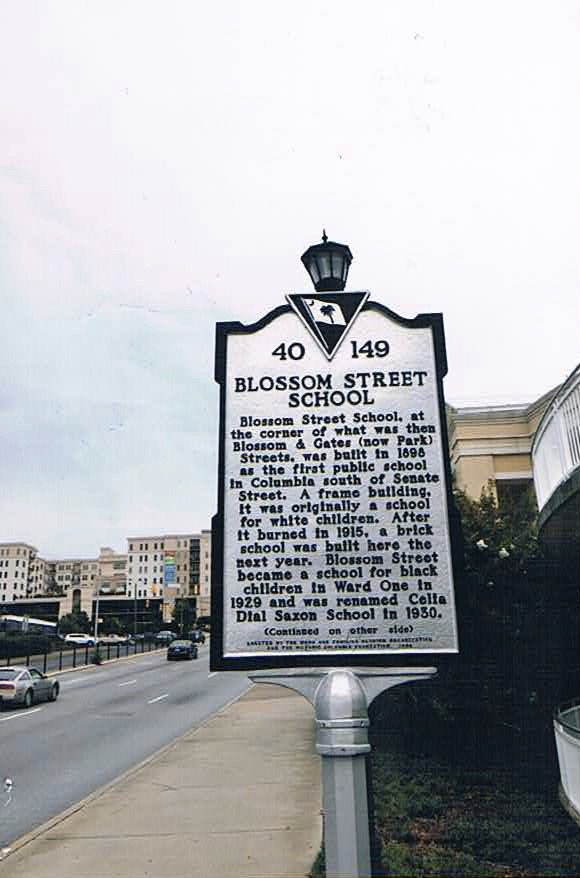

Every day thousands of students walk by the Strom, and in doing so, they also walk by this sign:

This is South Carolina Historical Marker 40–149. It honors the Celia Dial Saxon School, which opened in 1929 to the children of an African American community called Ward One. Most students don’t know this sign exists.

Most students don’t know the Celia Dial Saxon school ever existed at all and they definitely don’t know that the Celia Dial Saxon School was closed in 1968 and demolished in 1974. Most students don’t even know that it wasn’t until 2003 that construction on the Strom began.

See, the ugly truth about the Strom Thurmond Fitness Center (ugh, well, you know, besides the name) is that it sits on stolen property. And so does the University of South Carolina Koger Center (performing arts), the Carolina Coliseum (basketball), and the Darla Moore School of Business (exactly what it sounds like).

In the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, “urban renewal” struck Columbia, South Carolina. Before the 50s, you could divide the city of Columbia into three regions: the west, which consisted of a black community called Ward One, the middle, which was home to the University of South Carolina, and the east, home to many white families of university faculty and staff.

But in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, the residents to the west of USC – the black community – were told to leave. The district of Ward One had been deemed “blighted” by the state. Residents were told their homes, schools, churches, and businesses would be demolished for their own good, for their own safety. The community, however, was never rebuilt. Instead, the land was reabsorbed by the University of South Carolina, a campus that the residents of the Ward One community were never allowed to step foot on. Many Ward One residents never returned to Columbia after 1975.

In 2015, I joined a class at the University of South Carolina called “Critical Interactives: Ward One.” Half of the class was comprised of media artists, journalists, and historians. The other half of the class consisted of people like me: computer science majors looking to learn a brand new iOS programming language called Swift.

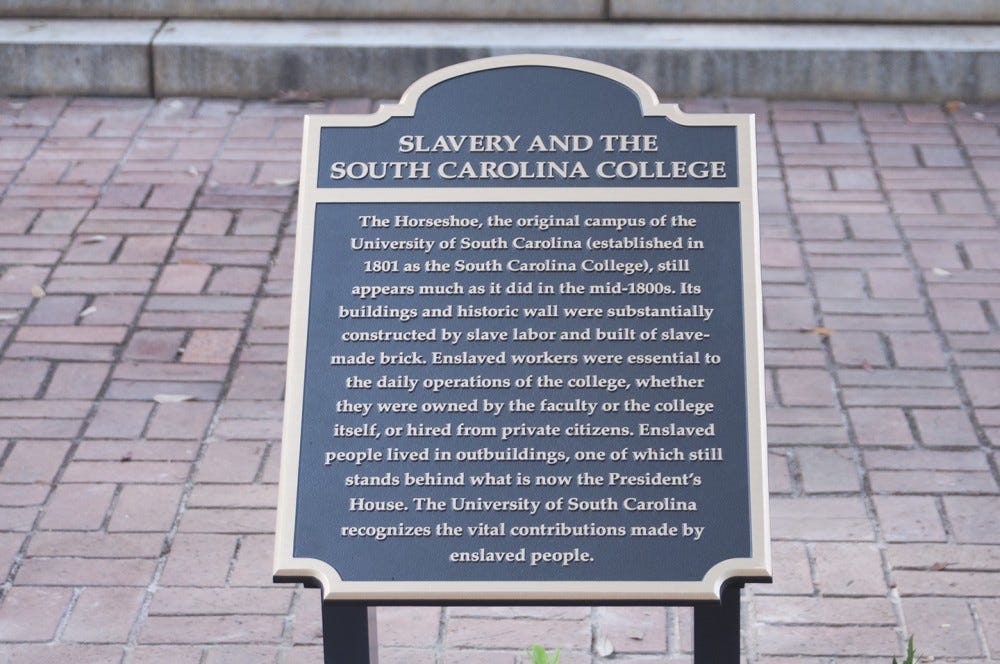

The goal of the project seemed simple enough: build an interactive app ~experience~ which conveys the history of the Ward One community. We kept saying “a history museum but on your phone.” We wanted to allow USC students and the broader community to know more about the history of their favorite places, and particularly, the role race had played in the formation of the university. Our university had just installed a sign at the front entrance of the university acknowledging that the “beautiful part of campus” had been built by slaves, and we were hopeful to ride the coattails of our all white, mostly male, grin-and-bear-it-til-its-not-awkward-anymore administration.

We were balancing interests: what the university administration would be willing to support, what students would interact with, and what the living residents of Ward One and their children wanted.

Together we thought we could hack this hard problem. With skills and experiences in so many disciplines, surely we would be thoughtful with this thing we were building. Our class was also all white.

What we ended up building was, arguably, cool from a tech standpoint. It has fairly good geolocation (good for walking tours around campus) in a place where geolocation had been historically difficult, we had cool augmented reality tools where you could overlay archival photos on what your camera was seeing, and had collected a bunch of new documentary video and audio from the remaining living residents of the Ward One community.

I remember demo-ing the app at a showcase towards the end of the semester. Some university administrators were there, my parents were there, and most of all, the members of the Ward One community were there. They loved it. It was like magic to them, seeing their childhood home come to life on a screen.

At the end of the event, we asked for feedback from the Ward One residents. There was one piece that has stuck with me, that came from 72 year old Mattie Johnson Roberson: “We don’t want this app to make anyone feel bad, we just want to show people why we were proud to live in Ward One.”

We had work to do.